leagueoflegends-optimizer

League of Legends Optimizer using Oracle Cloud Infrastructure: Real-Time predictions

Recap and Introduction

Welcome to the fifth article of the League of Legends Optimizer series!

In this article, we’ll test all the work that we’ve done in this article series. We’ll see how these models that we’ve created make predictions that make sense. In short, we’ll have a League of Legends companion in one of my games, and we’ll be able to see how the model reflects the state of a game at any point, and is able to predict the outcome of the game (either a win or a loss). So, without further ado, let’s get into it.

Connecting to the Live Client Data API

To extract live game information, we need to access the Live Client Data API from Riot Games.

The League Client API involves a set of protocols that CEF (Chromium Embedded Framework) uses to communicate between the League of Legends process and a C++ library.

Communication between the CEF and this C++ library happen locally, so we’re obligated to use localhost as our connection endpoint. You can find additional information about this communication here.

You can also refer back to article 4, where I explain the most interesting endpoints that we encounter when using the Live Client Data API.

For this article, we’ll use the following endpoint:

# GET https://127.0.0.1:2999/liveclientdata/allgamedata

# Sample output can be found in the following URL, if interested. https://static.developer.riotgames.com/docs/lol/liveclientdata_sample.json

# This endpoint encapsulates all other endpoints into one.

When we join a League of Legends game, the League process opens port 2999. We’ll use this to our advantage and we’ll make recurring requests to localhost:2999 to extract live match information and incorporate it into our ML pipeline. The result from our ML model will tell us if we’re likely to win or lose.

Architecture

In order to make requests properly, we need to access localhost as the calling endpoint. However, we may not want to access data on a local computer where we are playing (as computer resources should be used to get maximum game performance). For that, I have created an architecture which uses message queues and would allow us to make requests from any machine in the Internet.

For this architecture proposal, I’ve created two files, which you can find in the official repository for this article series under the src/live_client section: live_client_producer.py and live_client_receiver.py.

Producer

The producer is in charge of making requests to localhost and storing them without making any predictions itself. The idea behind this is to allow the computer where we’re playing League to offload and concentrate on playing the match as well as possible, without adding extra complexity caused by making ML predictions (which can take quite a lot of resources).

Therefore, we declare the main part of our producer this way:

while True:

try:

# We access the endpoint we mentioned above in the article

response = requests.get('https://127.0.0.1:2999/liveclientdata/allgamedata', verify=False)

except requests.exceptions.ConnectionError:

# Try again every 5 seconds

print('{} | Currently not in game'.format(datetime.datetime.now()))

time.sleep(5)

continue

# Send to RabbitMQ queue.

if response.status_code != 404:

to_send = build_object(response.content)

send_message('live_client', to_send)

time.sleep(30) # wait 30 seconds before making another request

We need to consider that, if we’re not inside a game, we’ll get a ConnectionError exception. To avoid this hardware interrupt, we catch the exception and keep making requests to the endpoint until something useful comes in.

For this, I’ve chosen RabbitMQ message queues a very simple and efficient solution to store our results into a queue. This ensures the following:

- Accessing and consuming the data present in the queues from any IP address, not only localhost

- Message order is guaranteed, should we ever need to make a time series visualization of our predictions. Therefore, we declare our message queues.

_MQ_NAME = 'live_client'

credentials = PlainCredentials('league', 'league')

connection = pika.BlockingConnection(

pika.ConnectionParameters(

'{}'.format(args.ip),

5672,

'/',

credentials))

channel = connection.channel()

channel.queue_declare(queue=_MQ_NAME)

Note that, in the above code snippet, we need to create a PlainCredentials object, otherwise authentication from a public network to our IP address where the producer is located would fail. Check this article out to learn how to set up the virtual host, authentication, and permissions for our newly-created user.

Additionally, every object that comes in needs to be processed and ‘transformed’ into the same structure expected by the ML pipeline:

# We remove useless data like items (which also cause quotation marks issues in JSON deserialization)

def build_object(content):

# We convert to JSON format

content = response.json()

for x in content['allPlayers']:

del x['items'] # delete items to avoid quotation marks

built_obj = {

'activePlayer': content['activePlayer'],

'allPlayers': content['allPlayers']

}

content = json.dumps(content)

content = content.replace("'", "\"") # for security, but most times it's redundant.

print(content)

return content # content will be a string due to json.dumps()

And finally, we declare a function that takes the message in string format, and inserts it into the message queue, ready to be consumed.

def send_message(queue_name, message):

channel.basic_publish(exchange='', routing_key=queue_name, body='{}'.format(message))

print('{} | MQ {} OK'.format(datetime.datetime.now(), message))

As we’ve built our message queue producer, if we run this while in a game, our ever-growing message queue will store messages even if no one decides to “consume” them and make predictions. Now, we need to do exactly this through a consumer.

Consumer

In the consumer, we’ll connect to the RabbitMQ server. This server doesn’t necessarily need to be located where we run our producer module. It can be anywhere just like if it was an Apache web server. Just be sure to that the connection in the producer and consumer both point to the same server IP address for RabbitMQ. We’ll make predictions with the light model (trained with 50.000 rows from our original dataset, as using a bigger model would yield higher prediction times) we trained in article 4:

# We load the AutoGluon model.

save_path = args.path # specifies folder to store trained models

_PREDICTOR = TabularPredictor.load(save_path)

def main():

try:

# localhost if the rabbitmq server is located in the same machine as the receiver.

connection = pika.BlockingConnection(pika.ConnectionParameters(host='localhost', heartbeat=600, blocked_connection_timeout=300))

channel = connection.channel()

# declare queue, in case the receiver is initialized before the producer.

channel.queue_declare(queue='live_client')

def callback(ch, method, properties, body):

print('{} | MQ Received packet'.format(datetime.datetime.now()))

process_and_predict(body.decode())

# consume queue

channel.basic_consume(queue='live_client', on_message_callback=callback, auto_ack=True)

print(' [*] Waiting for messages. To exit press CTRL+C')

channel.start_consuming() # we listen 24/7 for new messages in the live_client queue

except pika.exceptions.StreamLostError:

connection = pika.BlockingConnection(pika.ConnectionParameters(host='localhost', heartbeat=600, blocked_connection_timeout=300))

Note: if you run into ‘connection reset’ error, check out this documentation piece on pika which adds some parameters to the pika ConnectionParameters object to ensure well-behaved connections.

Every time we consume a message from the queue, we predict the outcome using our AutoGluon model, by calling process_and_predict:

def process_and_predict(input):

json_obj = json.loads(input)

team_color = str()

for x in json_obj['allPlayers']:

if x['team'] == 'ORDER':

team_color = 'blue'

else:

team_color = 'red'

print('Team {}: {}'.format(team_color, x['championName']))

# Timestamp given by the Live Client API is in thousands of a second from the starting point.

timestamp = int(json_obj['gameData']['gameTime'] * 1000)

data = [

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['magicResist'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['healthRegenRate'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['spellVamp'],

timestamp,

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['maxHealth'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['moveSpeed'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['attackDamage'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['armorPenetrationPercent'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['lifeSteal'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['abilityPower'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['resourceValue'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['magicPenetrationFlat'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['attackSpeed'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['currentHealth'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['armor'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['magicPenetrationPercent'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['resourceMax'],

json_obj['activePlayer']['championStats']['resourceRegenRate']

]

# We build the structure as our ML pipeline expects it (column names, and order).

sample_df = pd.DataFrame([data], columns=['magicResist', 'healthRegenRate', 'spellVamp', 'timestamp', 'maxHealth',

'moveSpeed', 'attackDamage', 'armorPenetrationPercent', 'lifesteal', 'abilityPower', 'resourceValue', 'magicPenetrationFlat',

'attackSpeed', 'currentHealth', 'armor', 'magicPenetrationPercent', 'resourceMax', 'resourceRegenRate'])

prediction = _PREDICTOR.predict(sample_df)

pred_probs = _PREDICTOR.predict_proba(sample_df)

expected_result = prediction.get(0)

if expected_result == 0:

print('Expected LOSS, {}% probable'.format(pred_probs.iloc[0][0] * 100))

else:

print('Expected WIN, {}% probable'.format(pred_probs.iloc[0][1] * 100))

print('Win/loss probability: {}%/{}%'.format(

pred_probs.iloc[0][1] * 100,

pred_probs.iloc[0][0] * 100

))

And that’s the last piece of code we need for everything to work. Now, we can get into a game and run our producer code (in the machine where we play the League match) and the consumer (simultaneously, although not necessary) to get real-time predictions on the game.

The Setup

We initialize our producer and consumer processes:

# producer must be run in the same server as where we're playing League

python live_client_producer.py --ip="RABBITMQ_IP_ADDRESS"

# in this case, receiver is running in localhost (in the same server as the rabbitmq server).

python live_client_receiver.py --ip="RABBITMQ_IP_ADDRESS" -p="MODEL_PATH"

The Game!

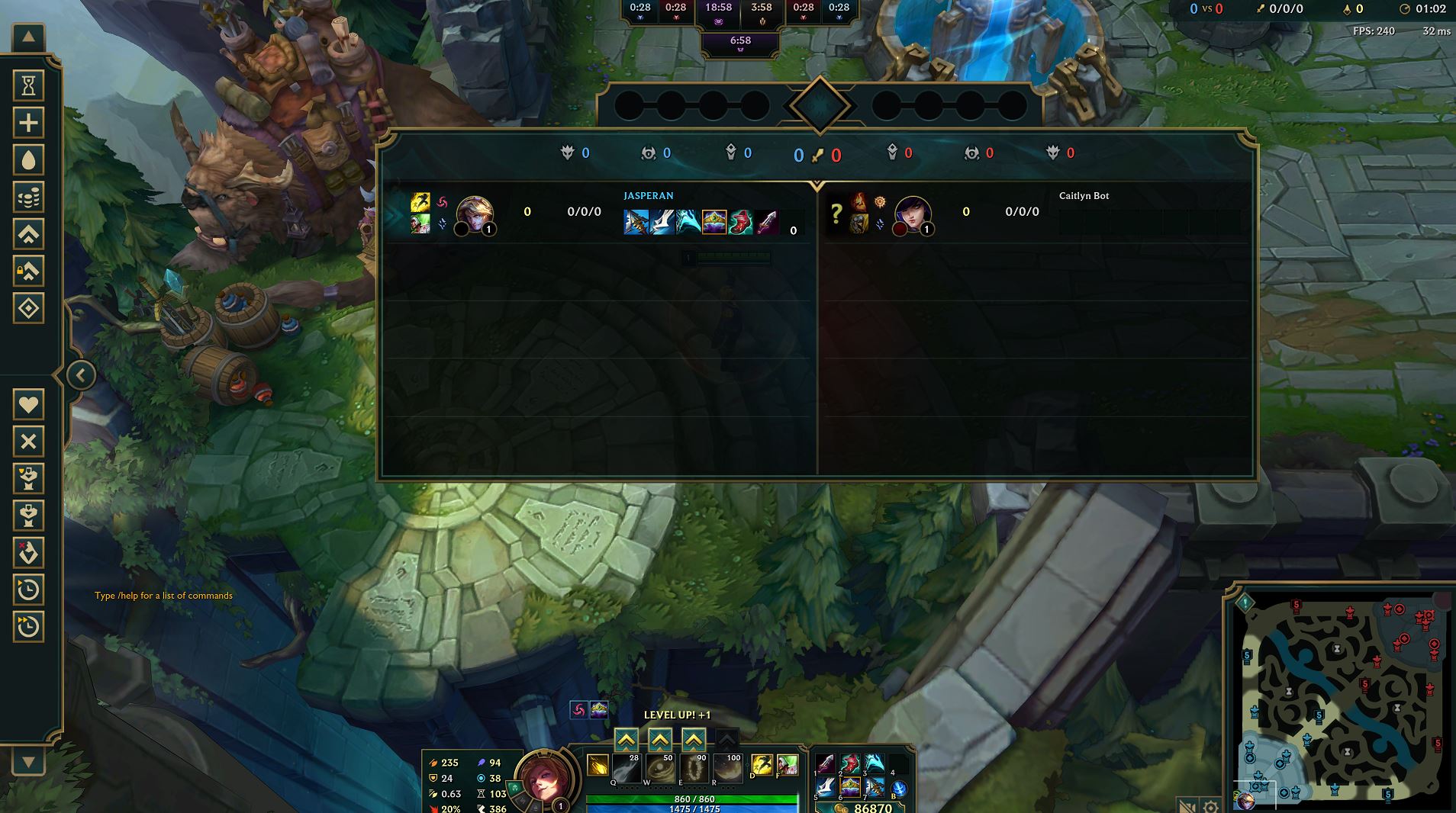

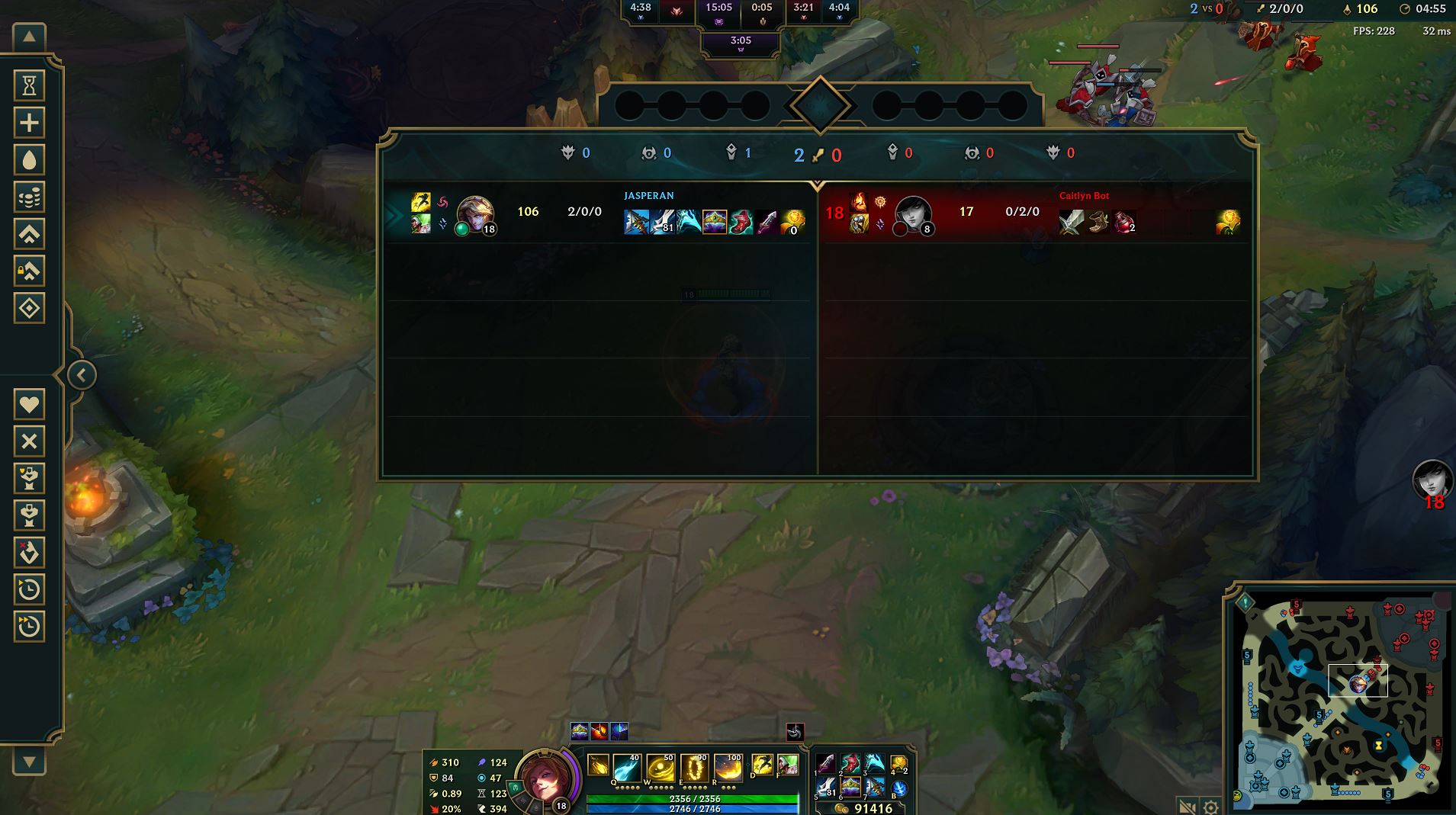

Since I’m using a lightweight model to make predictions, and training data is only 50000 rows, I’m expecting results to be roughly inaccurate. Therefore, to make things obvious and demonstrate the functionality, I’ve chosen to play a League match in the practice tool against an AI bot. This will allow me to level up quickly and buy items with gold from the practice tool, something that would take me about 30 to 35 minutes in a real match.

I chose to play Ezreal and bought a standard hybrid AD-AP build, which is especially good in lategame as cooldown reduction makes you a monster and it’d be really hard for enemies to catch me offguard with my E.

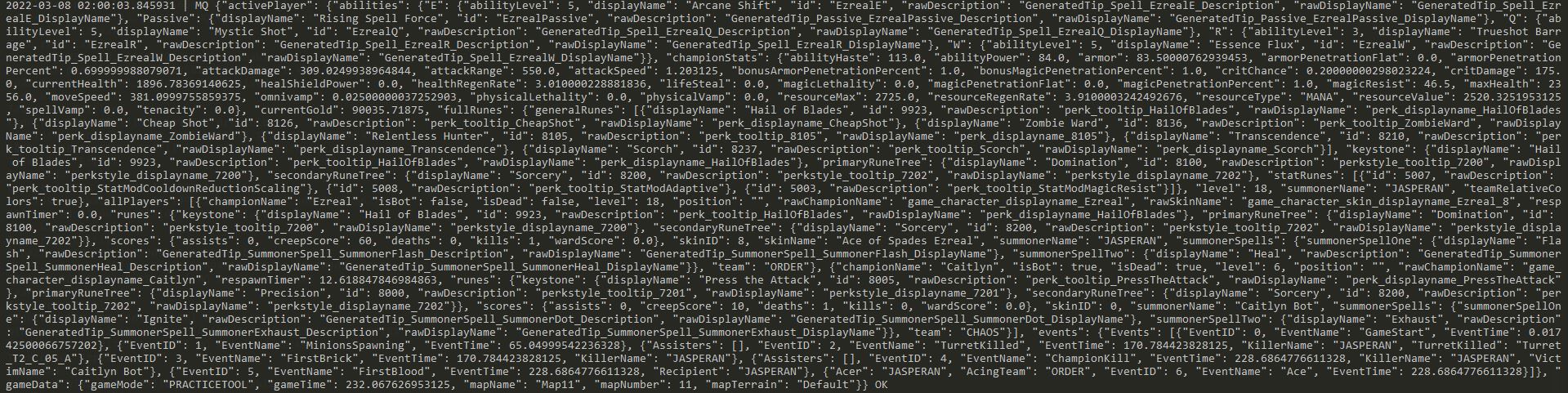

From the producer’s POV, we’re making requests every 30 seconds and expecting a prediction. This is the kind of data we’re storing in, and then consuming from our message queue:

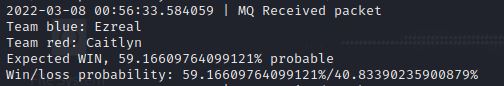

As we start the game, we get a very average 60/40% winrate probability. This is because Ezreal is usually superior in early game compared to Miss Fortune if we keep our distance. As training data comes from real Masters+ players, usually games are very quiet at the beginning and players perform very safely until midgame. Therefore, it makes sense that Ezreal starts with a bigger win percentage probability.

After starting the game, since we’re in the practice tool, I chose to go full-build and buy all items from the shop (the standard AD-AP build).

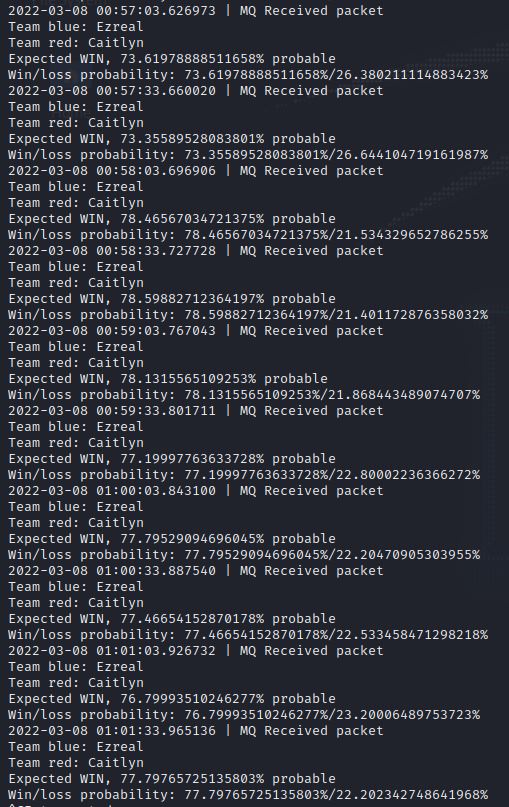

Immediately after the next request, the HTTP request fed the model my current stats, which were severely overpowered for the beginning of the game. If we review the statistics that are taken into account by our model, they are:

# Code from where we built the model

sample_df = pd.DataFrame([data], columns=['magicResist', 'healthRegenRate', 'spellVamp', 'timestamp', 'maxHealth',

'moveSpeed', 'attackDamage', 'armorPenetrationPercent', 'lifesteal', 'abilityPower', 'resourceValue', 'magicPenetrationFlat',

'attackSpeed', 'currentHealth', 'armor', 'magicPenetrationPercent', 'resourceMax', 'resourceRegenRate'])

Therefore, any statistic that’s considered an outlier from the interquartile range with respect to a specific timestamp will cause the model to consider it as an anomaly, and ultimately return a favorable prediction towards victory. In the case of my build, I’m deliberately increasing my movement speed, attack damage, armor penetration, lifesteal, ability power, attack speed, maximum mana (resourceMax), and magic penetration percentage. To make this clearer, I also added 17 levels to my match level, which in turn increased my magic resistance, armor and maximum health. This will “trick” my model into seeing all my values are way above average for the duration of the game I’ve been playing.

Consequently, the predicted winrate spiked to about 70% and stayed that way during the rest of the match:

As I’m only considering player statistics, killing my AI opponent didn’t give me any additional win probability, as kills, assists, deaths, vision score, etc. aren’t considered in this model. Also note that the model that’s making the predictions was trained with only 50.000 rows, instead of the tens of millions of rows we had in our bigger model. Surely predictions would yield better results if we used the bigger model; we just didn’t do that in this article since prediction times would increase significantly.

I leave this task (which should be fun enough with all the data you have available in the official repository for this article series) to you: trying to improve the current model by adding more variables like:

- Kills

- Deaths

- Assists

- Vision Score

- Crowd Control score

- Player level

You’re welcome to make an open source contribution to the repository! It’s never too late to get into open-source with us at Developer Relations @ Oracle.

I really hope that you enjoyed reading and learning about League of Legends in this article series. We built something truly amazing from scratch in a couple of months.

How can I get started on OCI?

Remember that you can always sign up for free with OCI! Your Oracle Cloud account provides a number of Always Free services and a Free Trial with US$300 of free credit to use on all eligible OCI services for up to 30 days. These Always Free services are available for an unlimited period of time. The Free Trial services may be used until your US$300 of free credits are consumed or the 30 days has expired, whichever comes first. You can sign up here for free.

Join the conversation!

If you’re curious about the goings-on of Oracle Developers in their natural habitat, come join us on our public Slack channel! We don’t mind being your fish bowl 🐠

License

Written by Ignacio Guillermo Martínez @jasperan, edited by Erin Dawson

Copyright (c) 2021 Oracle and/or its affiliates.

Licensed under the Universal Permissive License (UPL), Version 1.0.

See LICENSE for more details.